The Concertina's Darwinian Life in Ireland:

Growth, Decline and Regeneration

The Concertina

|

The concertina was invented in 1829 (the same year the accordion was patented) by the Englishman, Sir Charles Wheatstone. It was improved by the Germans and further improved, in turn, by the English. The full name of the instrument played in Irish Traditional Music today is the Anglo-German concertina. The German inventor, Carl Uhlig, was from Saxony – so it could have been named the Anglo-Saxon concertina. But in any case, Anglo-German is usually shortened to the Anglo Concertina.

It's a very Victorian instrument (though invented nine years before her ladyship ascended the throne). Its very name – concertina – sounds like a Victorian neologism. Concertinas also have the pre-electronic mechanical miniturization beloved by Victorian tinkerers with lots of parts stuffed into a small space – good goods in small parcels. And they were relatively inexpensive. They became very popular both in Victorian drawing rooms and among the working class. They were particularly identified with the Salvation Army and with sailors (with the Army and the Navy, as it were). A Salvation Army journal in 1911 listed the instruments attractions:

No instrument is at the same time so portable, powerful, cheap and easily manipulated as the concertina. |

For various reasons including the arrival of the phonograph and radio, the replacement of the music hall by the cinema and competition from improved accordions, the concertina lapsed into obscurity in the 20th century and most of the major British manufacturers went out of business in the 1920s.

Thus, it is extraordinary that the concertina should survive in such a prominent role in Irish music in County Clare. Charles Wheatstone hadn't designed the instrument with Irish Traditional Music in mind. And Clare was not exactly at the center of Victoria's empire. In fact, de Valera's 1917 election in East Clare showed that the place was among the most gangrenous extremities of the empire, in an advanced stage of auto-amputation, in fact. Of course, it was may have been Clare's isolation that allowed for the preservation of the concertina's role in ITM there. Linguistic and cultural archaisms frequently survive in peripheral and/or remote areas – witness the survival to this very day of Elizabethan English on the isolated Smith and Tangier islands in Maryland's Chesapeake Bay. |

The Adoption of the Concertina into Irish Traditional Music

From the earliest days of country-house dancing in west Clare, it is perhaps the concertina that can claim to be at its musical heart … Although the fiddle and flute can claim honoured places in west Clare's musical history, the modest German concertina was the people's favourite for the best part of a hundred years. (Taylor: 209)

|

Concertina historian, Dan Worrall, says that there was nothing special about the arrival and flowering of the concertina in Clare – it was a popular instrument throughout Ireland in its heyday from about 1870 through the 1930s.

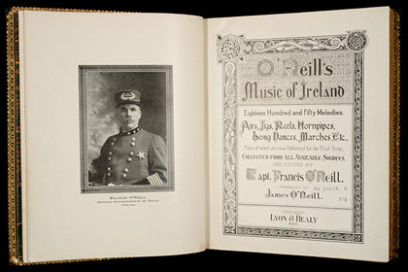

The instruments used were cheap German two-row affairs that were easy to learn. They swept the country. Some saw them in the same light as invasive foreign flora displacing indigenous plants. A 1897 letter to a London music magazine: Cheap German concertinas are the chief instruments occasionally (sic) seen. I cannot but regret that the national harp and bagpipes seem to have disappeared in favour of these importations from the Fatherland [Germany]. (Worrall: 201) One didn't have to be anti-German to resent the invasion. The Gaelic League saw them as foreign and outside the tradition, as did the premier tune-collector of the time, Chicago Police Chief Francis O'Neill who ignored their existence. They were as unwelcome in the day as an electric guitar would be at a session today.

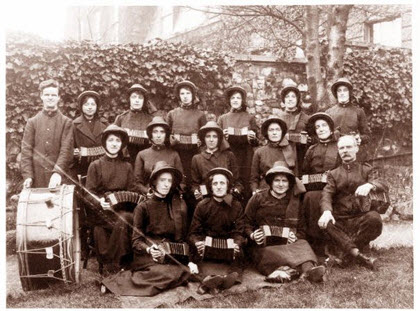

But their popularity continued to grow. According to two Clare music historians: Here at one time, in the first three decades of this [20th] century, there was a concentration of fiddle and concertina playing. It was, as someone put it, a "nest of concertinas." (Worrall: 201) Concertinas were particularly popular with women. The late player Tommy McCarthy said of his hometown Sheane:

'Twas very much a woman's affair … Around Sheane alone … every woman used to play one nearly. (Worrall: 236) They found favor with women since they were cheap enough to be bought with the egg and butter money, were small and portable and had a reedy sound like the pipes.

There is also a theory that since they were new on the scene, women didn't have to contest a long-established tradition of male hegemony. This last bit is not convincing since the harp, the oldest identified Irish instrument of all, is now pretty much dominated by women, in my experience. German concertinas were cheap and, with their paper bellows, correspondingly flimsy. In the hands of an enthusiastic player, they would sometimes only last for a single night's house dance. Maybe the fact that they would care for the delicate instrument better and make it last longer made women more accepting of them than men. |

This would fit with Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin's description of the gendered nature of the concertina's usage. He reports that the concertina was known as a bean chairdín (pronounced very roughly as "ban kordeen" and meaning a she-accordion or accordionette, an accordion for women). He paints a cosy domestic picture of the concertina's pride of place in West Clare kitchens (even in non-musical ones where they were kept for visiting players):

A special clúid, or alcove, was constructed for the concertina in the inner wall of the hearth, close to the open fire. (Ó hAllmhuráin: Web Site) It was the little engine that could. Its small frame could produce a robust enough sound, particularly when augmented by expert octave playing, to provide the music for house and crossroads dances on its own. And it was just as well that it could since some house-dance physical arrangements couldn't accomodate a band. In a case of organic Darwinian adaptation, it was perfectly suited to to its environment.

Is ann sin ar feadh na mblianta a mhair sé cois tine faoi choimirce bhean an tí ina chlúid shámh chompordach ag gabháil fhoinn lena bheatha a shaothrú. (It was there for many years that it lived in its cosy fireside clúid tended by the mistress and making music for its keep.) It even drove out competitors (such as the pipes, to Chief O'Neill's great displeasure). But such a creature is uniquely dependent on its habitat and fatally vulnerable to environmental degradation. In the 1930s, the attack came, big time. Mother Ireland and Mother Church conspired to make sure that de Valera's vision of a countryside "joyous … with the laughter of happy maidens" was clerically supervised to the extent that the maidens' merriment came from consorting with "athletic youths." (De Valera 1943) The cosy kitchen was doomed to give way to the drafty hall; the solo concertina to the céilí band.

|

The Destruction of the Concertina's Habitat

The music was to ripped from its social fabric by the very agencies which proposed to promote all things Irish – the Catholic clergy and the Fianna Fáil party. (Curran: 57)

|

It is said that there are seven deadly sins. Which is a load of bull. There's only one: Lust. Who gives a toss about: Gluttony (not too many skinny preachers); Greed (is good); and so on for Sloth, Wrath, Envy, Pride?

Dancing was condemned as Lust's procurer – the vertical expression of a horizontal desire; foreplay in front of closed doors. A good barometer of the repressiveness of a religion is its attitude towards dancing. Catholicism is nowhere near the worst of a sorry lot though the Council of Irish Bishops warned in 1927 that: The evil one is ever setting his snares for unwary feet. (Hogan: 63) It might be noted that the owners of the unwary feet, people the Church determined to treat as children (or as sheep since they tellingly called them the flock) were not hayseed hicks, cretinous culchees or, to appropriate a pejorative putdown from The Midnight Court, brutish bogmen from Coora in the County Clare.

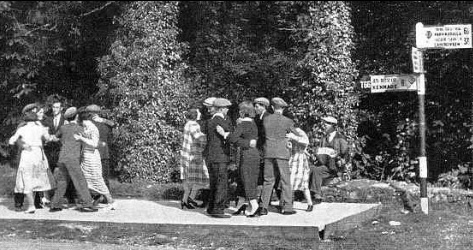

The people were aware of goings-on in the world (which is partly what the church feared). Some were returned emigrants and most had close relatives in Britain or America. Literature in Irish evidences an internalized world map where Springfield Massachusetts, for instance, is closer than Dublin. As for Dublin, it is documented that the famed Mrs. Crotty, concertina player par excellence, travelled there frequently from Clare and met up with musicians from all over. Indeed, the widespread availability of the instrument she played as well that of fiddles and flutes betokened internationalism since they were the cheap products of the Industrial Age factories of Britain and Germany. (It is interesting that the Anglo concertina took the diametrically opposite path to most consumer artifacts: It first gained popularity through the mass production of industrial factories and evolved from there to being mostly made by small-establishment craftsmen; went from cheap and insubstantial to relatively expensive works of the craftman's art with a waiting list that can stretch into years.) The various photographs of outdoor dancers on this page show the participants dressed smartly for the occasion. It is amusing to note that men invariably wore the ubiquitous cloth cap (variously: caipín, cáibín, caubeen) while women went hatless.

Whether deliberately intended as a statement or not, this was exactly opposite the going-to-Mass norms noted in the companion essay where the Church sought to instill chastity and humility by requiring women to cover their heads and the men to bare theirs. (Internal photos of house dances appear to be rare, perhaps for technological reasons. Men probably wore caps there too. Perhaps the only question at issue is what happened to the cap at the bedding-down part of the process.) Still, in spite of its general antipathy to the proceedings and its incredibly undemocratic assumption that it had a literally God-given right to oppressively police the population, the Catholic Church in Ireland never went so far as to actually ban dancing as some other churches have done. But the idea that the he's and the she's in the flock could use entertaining and aerobic means to help sort themselves out partnerwise without clerical supervision drove the morality police bananas: The heart and spirit gave way to a sort of terrorism before the priest. In his day of dominance, he did much to make Irish local life a dreary desert. He waged war on the favourite cross-roads dancing. (Brennan: 123) Not few are the pipers and fiddlers thus forced into exile by the unwarrantable harshness of the clergy … To such a degree had the sense of wrong rankled in their breasts that some now in Chicago and in the enjoyment of prosperity decline to figure in the programmes of church entertainment. (Brennan: 124) |

Wooden roadside platforms were set on fire by curates: surer still, the priests drove their motorcars backward and forward over the timber platforms; concertinas were sent flying into hill streams, and those who played music at dances were branded as outcasts. (Hogan: 74) Was it coincidence or was it just an extra touch of misogynistic finesse that the instrument landing in the river was the woman's instrument, the bean chairdín?

The Church had willing accomplices in the De Valera, Cosgrove and Costello governments, the secretive Knights of Columbanus, the Catholic Truth Society and even the Gaelic League (which was as so hidebound to regard set dances as foreign while the London-born Céilí dances were supposedly native). Even the establishment Irish Times, with its largely Protestant readership, got in the act. In an editorial in March 1929 it speculated that: the banning (by law if need be) of all night dances would abolish many inducements to sexual vice. (Brennan: 125) The end result of these unholy alliances was the execrable Public Dance Halls Act of 1935:

The act was draconian, making it practically impossible to hold dances without the sanction of the trinity of clergy, police and judiciary. With its passing, the hierarchy could rest content that its proposals for the legal control of personal morality had, without serious modification, been transformed into law. (Smyth: 54) As a sidebar, the goings-on in cars parked darkly outside dance halls (or in far quiet lanes) has been a source of adult high anxiety ever since the auto was invented. And so, canoodling in cars was covered by the Act – which got around privacy concerns in policing that particular sin site by redefining a car as a street (no kidding: "the word street in this section [shall] include a motor car").

"This allowed the police to treat a car as a public place and use their discretion as to the nature of behaviour within." (Smyth: id.) The land of James Joyce evidently has a government bureaucracy that uniquely knows how to use language creatively. In more general terms, under the Act: it seems that in most instances the only person in the community who could actually obtain a dance hall license was the Parish Priest, who often promptly built a new parish hall, started charging a ticket tax, and called the local Guard to end any other dancing taking place. (Curran: 57) It is ironic that, in 1921, it was the thuggish British Black and Tan militia had raided house dances, a force that is second only to Oliver Cromwell in Irish demonology. Fifteen years later, the Tans were replaced by a homegrown vigilante force composed of "angry parish priests." (Ó hAllmhuráin 1998: 111) The All Blacks taking over from The Black and Tans.

Depending on who you read or listen to, the enforcement of the Act either killed the house dances and the way of life that went with them or hastened a process along that was occurring independently. Either way, the intention, result and culpability are similar. Noted Clare concertina and fiddle player, Junior Crehan (1908-2008), lamented their passing: About 1936, the house dances were banned by the government and the Dance Hall Act was passed. The halls were built and jazz and foxtrots were the dances and the country man couldn’t cope. It was the greatest crime ever committed against our culture and way of life. The country house was our workshop and school. It was there we learned our music song and dance. At that time and for a good few years after music song and dance faded away and most of my pals who played with me emigrated to America. It was a sad lonesome time. (Worrall: 239) |

Maladaptation of the Concertina

|

Organisms that are well adapted to a particular environment can be much less fit if environmental conditions change. Fish don't do well if the lake dries up.

Among the common Irish musical instruments, the concertina was the least well adapted to the change wrought by the Dance Halls Act. Most of the old (German) concertinas were two row instruments in the keys of C and G. Most Irish tunes are in G, D or A (corresponding to the three lower open strings of the violin). The concertina had the key of G's F# but lacked the C# and G# needed for the D and A keys. In ensemble playing, the concertina player would be out of luck with tunes in D and A. It was common for concertina players to play solo for the house dances (obviating the need for a band). Dancing feet don't mind if a tune is transposed down from D to C as long as it sounds good and the rhythm works. After the war, concertinas that were more chromatic but had been discarded as no longer fashionable began showing up in London's antique and pawn shops. Clare immigrants in London bought them for the folks back home. |

However, the added sharp buttons were in the outside third row and this required players with muscle memory acquired over a lifetime to change their basic playing techniques – in order to play in an environment in which they were not particularly comfortable to begin with.

As the dances moved from house to hall, the concertina and concertina player were left at home. Céilís in parish halls required a more robust source for the music. Thus was spawned the era of the céilí band, which combined a plethora of instruments such as accordions, fiddles, flutes, piano and drums but very few concertinas, a setup that is still mostly true today. |

The Revitalization of the Irish Anglo-German Concertina

|

In the rest of Ireland outside of Clare, the once ubiquitous Anglo-German concertina had become little more than a nostalgic memory by the middle of the twentieth century. (Worrall: XXX). There was just one last surviving enclave that had:

the continued use of the concertina by a few hardy traditional musicians in County Clare. (Worrall) Nobody seems to have an adequate explanation why Clare became the redoubt that it was. The late arrival of electricity (which curtailed the spread of phonographs and radios) may have been a factor. But Clare wasn't alone in getting the electric late. Poverty and remoteness: There was nothing special about Clare there either.

The natural world again may provide the clue. It would not be surprising to find the last survivors of a disappearing species in the area in which they were most numerous in their heyday. The area might have lingering remnants of its prior environmental hospitality and the genetic diversity provided by a large population might mean that a small but critical mass would make it through the apocalypse. The following account, adapted roughly from Dan Worrall, can be seen as an example of this process in action: The concertina’s barest survival in Ireland and its recent resurgence, was largely enabled by the efforts of a few remaining traditional musicians in those rural western areas (predominantly County Clare) who stuck with the music, and the concertina, in the very lean years of the 1930s to 1960s. By 1970 the concertina’s use may have been measured in a few dozens of players in County Clare. Absent the stick-to-it-edness of players such as Mrs. Crotty, Paddy Murphy, Packie Russell and Junior Crehan, it could all have so easily been lost. Because of the efforts of these few musicians, when a late 20th century revitalization came to Irish music, active, living proponents of the concertina still existed. The concertina revival in Ireland started from that core of survivors. |

The course of evolution of a species that is revived in a new environment may be channeled in a new direction.

So it was with the new generation of concertina players. Environmental changes included the disappearance of house dances, the introduction of fully chromatic instruments and competitions sponsored by bodies such as Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (The Musicians Society of Ireland). The link to dance became tenuous. The performance was for an audience of listeners rather than dancers. The style became more richly ornamented and virtuosic. It became less rooted. Even though local differences survive in Clare, the global music that expanded out from its small area necessarily lacks the sense of terroir associated with the micro-environments of its place of origin. It's like a small sharp bitmap photo on a computer screen. As you enlarge the picture, the sharpness progressively disappears in a process known as pixelation. Global Irish concertina music tends to be a pixelated version of the Clare original. It's still wonderful but it's an amalgam. And global the music has become. The revival has seen an explosion of new players not only in Ireland, but in England, continental Europe, North America, Australia, New Zealand and beyond. In the old days, Irish music on the concertina was a mere backwater of an instrument that was played, in different vernaculars, all over the world. Now: more than any other current genre of concertina playing, Irish Anglo-German concertina playing is driving the global revival of the instrument. (Worrall: 260) In addition to how unlikely it all is, it sounds kind of funny: Irish Anglo-German concertina playing. It's as if Senator George Mitchell had convened some kind of kumbaya session to bring together peoples with, let's call it, a complicated past. No doubt, the Reconciliation or Olive Branch Reel would be in the repertoire. See below for a slow version of the reel from Picton, New South Wales, with a kind of neat accompanying mimed commentary from the kid sitting on his ownio on the left.

It's an extraordinary legacy of the Clare stalwarts who kept a tradition alive through the lean years and an illustration of how, in mysterious and unlikely ways, a loved folk art can be regenerated. The local paper in the county is The Clare Champion. The saviors of the concertina are The Clare Champions. |

useful concertina and related links

Sources

- Brennan, Helen. 1999, 2001. The History of Irish Dance.

- De Valera, Éamon. 1943. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ireland_That_We_Dreamed_Of. This is often identified as De Valera's St. Patrick's Day 1943 "Comely Maidens" speech although he did not use that term.

- Eydmann, Stuart. The Life and Times of the Concertina: the adoption and usage of a novel musical instrument with particular reference to Scotland, Academic Dissertation from 1994 posted on line in August 2005.

- Hogan, Eileen. 2010. Earthly, Sensual, Devilish: Sex, 'race' and jazz in post-independence Ireland. Jazz Research Journal 4(1): 57-79.

- Ó hAllmhuráin, Gearóid. 1998. A Pocket History of Irish Traditional Music.

- Ó hAllmhuráin, Gearóid. 2005. Dancing on the Hobs of Hell: Rural Communities in Clare and the Dance Halls Act of 1935. New Hibernia Review. Winter 2005.

- Ó hAllmhuráin, Gearóid. 2009. Web Site: http://www.concertina.org/2009/12/05/clare-the-heartland-of-the-irish-concertina/

- Ó hAllmhuráin, Gearóid. 2011. Similar entries on the concertina in Fintan Vallely's Companion to Irish. Traditional Music (2011) and The Encyclopedia of Music in Ireland (2013) edited by Harry White and Barra Boydell.

- Smyth, Jim. 1993. Dancing, Depravity and All that Jazz: The Public Dance Halls Act of 1935, History Ireland Summer 1993.

- Taylor, Barry. 2013. Music in a Breeze of Wind: Traditional Dance Music in West Clare 1870-1970.

- Worrall, Dan. 2010. The Anglo-German Concertina: A Social History, Volumes I and II, Third Edition. Much of the material on the concertina in Ireland is reproduced at this link.