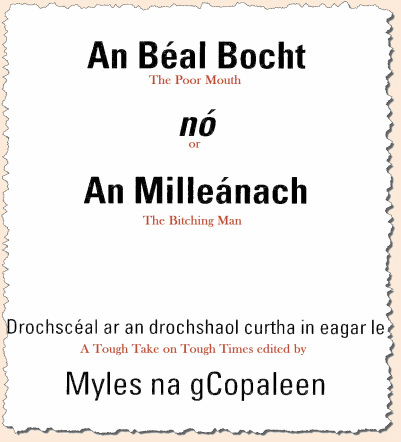

Language Note: The purpose of this page is to publish, with considerable contextual background, an otherwise inaccessible comic map from the Irish language novel of the 1940s, An Béal Bocht. The name of the book requires a bit of explanation of Irish grammar. The definite article in Irish is an but is pronounced like English on rather than an. Thus, the two books discussed extensively in this essay are An t-Oileánach and An Béal Bocht (The Islandman and The Poor Mouth). Also, the lower case "g" before the capital "C" in Myles na gCopaleen is a grammatical eclipsis signifying the genitive case – the word is pronounced Gopaleen.

myles na gcopaleen's Buried Map

|

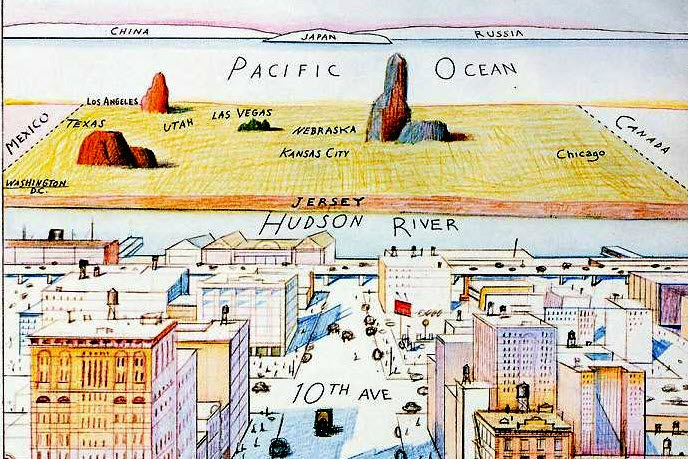

On March 29 1976, the cover of my favorite magazine, The New Yorker, depicted how a resident on 9th Avenue might view the world if he looked west. The cover was the work of illustrator Saul Steinberg and it resonated because, in a picture being worth a thousand words kind of way, it encapsulated a stereotype of the supposedly arrogant New Yorker.

It was a cartoon map of the world. Beyond the Hudson River, two blocks or so from resident's front door, the mind-map of the rest of the United States becomes a decidedly indistinct place. The resident had a vague of idea of there being places like Chicago, Vegas, Texas and the vast plains. Canada is somewhere to the north and Mexico to the south. The Pacific Ocean, perhaps only as wide as the Hudson, separates the United States from three flattened land masses labeled China, Japan and Russia. Europe doesn't figure. It was a neat concept and was widely imitated. But it was not original. The concept of distant places being out of focus in a local's world map had been used about thirty-five years earlier as a frontpiece of the Irish language novel, An Béal Bocht (The Poor Mouth) by Myles na gCopaleen (Myles of the Little Horses). |

Myles na gCopaleen was a pen name of Brian Ó Nualláin (Brian O'Nolan); Flann O'Brien was another. (One might note that, à la nom de plume in French, the Irish equivalent of pen name is ainm cleite

— literally, quill name, an appropriate archaism, perhaps, reflecting

the fact that Irish was a written language long before English was even a

linguistic zygote.)

The focus in the earlier illustration was diametrically opposite that of the New Yorker cover. The perspective is scrunched rather than stretched. Instead of distant places fading into indistinction, locations such as Springfiled Massachussetts were seen with an next-over-parish immediacy to the inhabitants of Ireland's Kerry, Connemara or Donegal areas (which themselves were within walking distance of each other). Just like the New Yorker cartoon, the map in An Béal Bocht satirized what it depicted. The parody works because the broad comedy contains more than a smidgen of truth. |

an Béal Bocht agus An t-oileánach

(THe Poor Mouth and the islandman)

|

Frank McCourt's Angela's Ashes ("worse than the ordinary miserable childhood is the miserable Irish childhood") gained international renown as the best known example of the Irish misery memoir. But before Angela's Ashes, there was a history of memoirs by rural authors from the Irish-speaking districts along Ireland's west coast, known collectively as the Gaeltacht (irish-speaking area) autobiographies, including:

The cover of An t-Oileánach, shown above, portrays the upright noble fisherman striding purposefully on his manly business in what seems like a sunny day. The rip-off cover of An BB distorts the original as if in a mirror darkly by showing the bent-over and half naked protagonist in the ceaseless lashing rain carrying the fruitlessness of his labor, a lousy little pinkeen on a string. In open mockery of An t-Oileánach, An BB is subtitled by the rhyming An Milleánach. The Island Man becomes the Bitching Man. An BB is further subtitled Droch-Scéal ar an Droch-Shaol (A Tough Take on Tough Times), a more integrated phrase in Irish than English since Scéal and Saol rhyme. Ó Criomhthain's most famous line comes at the end of An t-Oileánach where he explains and asserts: |

Scríobhas go mionchruinn ar a lán dár gcúrsaí d'fhonn go mbeadh cuimhne i bpoll éigin orthu … mar ná beidh ár leithéidí arís ann. (I wrote most minutely about our affairs so that they might be remembered in some hole or other … because there will never be our likes again.) (Ó Criomhthain: 256) Philip O'Leary, author of a massive three-volume historical review of Gaelic prose literature from 1881-1951, remarked trenchantly that:

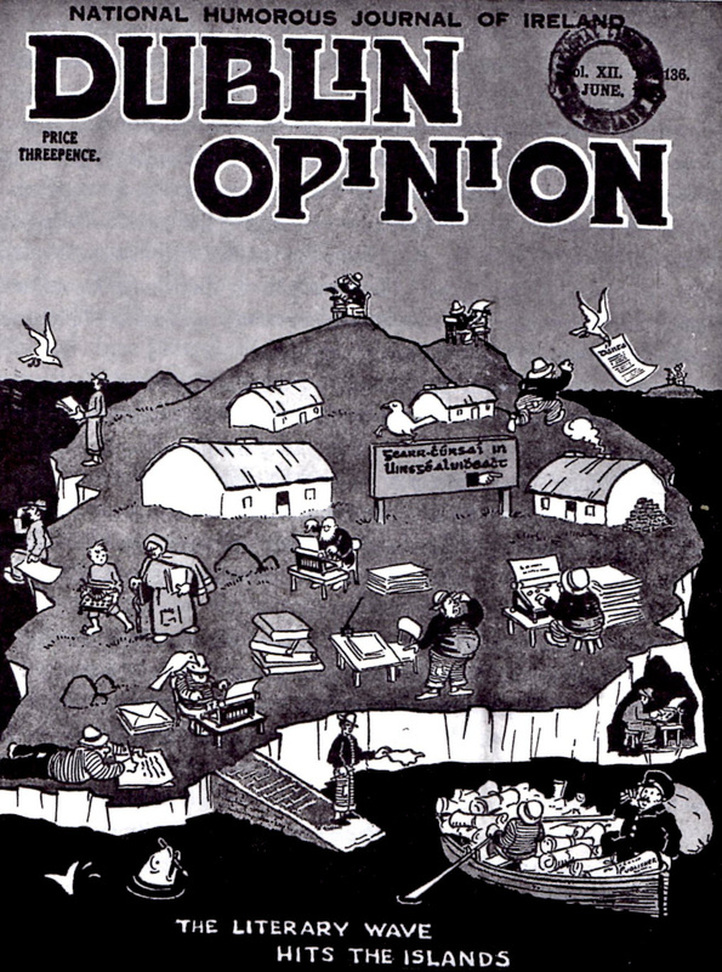

The more sardonic may well have felt that the Blasket Island sage, Tomás Ó Criomthainn, was utterly mistaken in the most famous pronouncement of his 1929 classic, An tOileánach, for with the steady ongoing production of these autobiographies, his like was most certainly being read if not seen again (O'Leary: 441) Foreshadowing An BB, a 1936 cover of the magazine, Dublin Opinion, caricatured the book-producing factory that the Blaskets had become. The whole island is busy writing and a laden boat exports the resulting manuscripts. The sign in the middle of the island advertises Short Courses in Novel Writing.

In any case, the line about there not being our likes again is mockingly repeated all over the place in An BB and is, predictably, the last line in the book. |

"Anró gaelach"

(Gaelic misery)

|

Pigs are big in An BB. The pig in the parlor is a touch touchy in an Irish context — and therefore a grand image for Myles to latch onto with gleeful gusto.

People are so dirty, houses (home to both pigs and people) so dark and the drowning rain so incessant, that it is hard to tell people and pigs apart. In Bónapárt's house, a government scheme is diddled out of £2 a head in child allowances when the inspector, repelled by the smell from conducting a close inspection, is scammed into believing that the dozen bodies lurking in the dark arse-end of the house ("i dtóin an tí") are kids jabbering away in English (for which the allowance is the reward) instead of the pigs that they really are. (Parenthetically, it might be noted that everything that happens in that house invariably occurs in its arse end and the house itself is located in the armpit of the glen.) One of the banbhs (young pigs) happened to escape in drag in his little suit into the rain-lashed night and wound up drowningly crawling into the house of neighbor Macsamailliún Ó Píonasa. As it happened, there was a bigshot academic there from Dublin with a tape recorder trying to coax Irish from the assembled locals who were made more taciturn than usual by being liquored up, at the ill-advised courtesy of the scholar. In the darkness, the little pig resembled a miserable drenched old man crawling in on hands and knees and babbling away at a mile a minute. The scholar couldn't make out a single word, which was terrific since he understood that good Irish was difficult and the best indecipherable. The upshot of the story was that the Dubliner got a "lovely learned" university degree out of it and Bónapárt 's grandfather, An Seanduine Liath (Old Greybeard), got a trip to Berlin to decipher the tape for a conference of experts (introducing a dissonant note into the novel since the image of Greybeard, ahem, living high on the hog in Berlin, on the pig's back, as it were – ar mhuin na muice – muddies the water in which the sodden sods of Corca Dhorcha were pictured as living). By the way, Myles loved trans-language slang. One cannot resist the temptation of adding

to his collection. The Irish word for pig is "muc" (pron., as one might suspect, "muck"). A

good name for the dirty pigs Myles features so heavily would be "mucky

mucs" and the confab in Berlin: Irish Language Muckedy Mucks Decode Mucky Muc's Irish Language (Festschrift zum achtzigsten Geburtstage An tSeanduine Léith am 29. März 1922. Berlin. Seiten 9-22).

On another occasion, the household mourned a swelling and smelling dead pig named Ambrose because – wait for it: "B'ait an mhuc é Ambrós agus ní dóigh liom go mbeadh a leithéid arís ann" (Ambrose was a special pig and I don't believe there would be his like again). Even alive, he smelled so bad that Charlie the horse wouldn't stay in the same house as Ambrose the pig. Dead, he stank up the place so much that the neighbors sold up and emigrated to America to get away from the stench. The twist and the sting in all of this is that Myles did not believe a word of what he writes. He held An t-Oileánach and its author in the highest esteem. In his newspaper column in 1957 he said of BB, his own book: This prolonged sneer, long out of print, will be republished shortly. My prayer is that all who read it afresh will be stimulated into stumbling upon the majestic book upon which it is based. (Ó Conaire: 122) |

But he and fellow writer Máirtin Ó Cadhain believed that the Gaeltacht population was being used as museum or mausoleum exhibits, preserved not in aspic but in pig shit and poverty. Their role was to satisfy officialdom and academic types that the precious Gaelic heritage was being conserved in its native milieu.

At one stage in the narrative in An BB, language tourists seemed to disappearing, leaving Bónapárt to wonder: Ba ghann na pinginí a d'fhágadar ina ndiaidh mar luach saothair do na bocthtáin a bhí ag feitheamh leo agus ag coimeád na Gaeilge céanna beo dóibh le míle bliain. … Bhí sé ráite riamh go mbíonn cruinneas Gaeilge (maraon le naofacht anama) ag daoine de réir mar bhíd gan aon mhaoin shaolta agus ó tharla scoth an bhochtanais agus na hanacra againne, níor thuigeamar cad chuige go raibh na scoláirí ag tabhairt airde ar … chríochaibh eile. An Béal Bocht in a nutshell. Myles' subversion was to piss all over the museum's literary show pieces in order to piss off its curators, patrons and assorted hangers-on. It was slagging on a grand scale. It's like denigrating the Mona Lisa in order to rile up the powers that be at the Louvre.

If the intended targets didn't rise to the occasion with appropriate and gratifying outrage, Myles was prepared to turn agent provocateur. In two separate letters to his publisher, he outlined the plan: If the book doesn't provoke a row with the die-hards, I will have to whip one up by showers of pseudonymous letters to the papers … whipping up a controversy in the papers about it under a thousand aliases. (Ó Conaire: 108, 104) He needn't have worried. The reviewer for the famous Bell literary magazine used, as it were, a pig-Latin bowdlerization of a famous Latin phrase De Disgustibus non Est Disputandum – i.e., There's no Accounting for (Bad) Taste – to explain how anyone could find the £2 scam described above "a screamingly humorous notion". (Ó Conaire: 110) In reply, Myles punningly referred to the magazine as An Bell Bocht.

Elsewhere on this web site, the text used for the Midnight Court is the one published by Risteárd Ó Foghlú (Richard Foley) in 1912. Ó Foghlú is brought up here because he published An BB's most negative review in the Irish Literary Review. Reading the book was a penance ("píonós"). He compared the virtual stink given off by the pig-infested houses to his experience of running past stinking tanneries and chemical factories on the Continent. He thought the book a disgraceful waste of scarce paper in wartime 1942. Predictably, Myles made sure the review was not buried in an obscure literary magazine by republishing it in his Irish Times column. (Ó Conaire: 110) There is almost no sex in An BB. Indeed, the Corca Dorcha residents are said to have only a vague understanding of the facts of life. Thus, while there is little amour in An BB, the book craps all over the amour propre of the Gaelic Irelander. The former didn't upset Ó Foghlú in the Midnight Court but the latter very much did in An BB. In this, he was the opposite to most of his contemporaries. While Frank O'Connor's translation of the Midnight Court was being banned, there didn't seem to be much official negative reaction to An BB (though this might have somethng to do with the fact that a translation that they could understand didn't appear until 1973). |

Myles' Buried Map

|

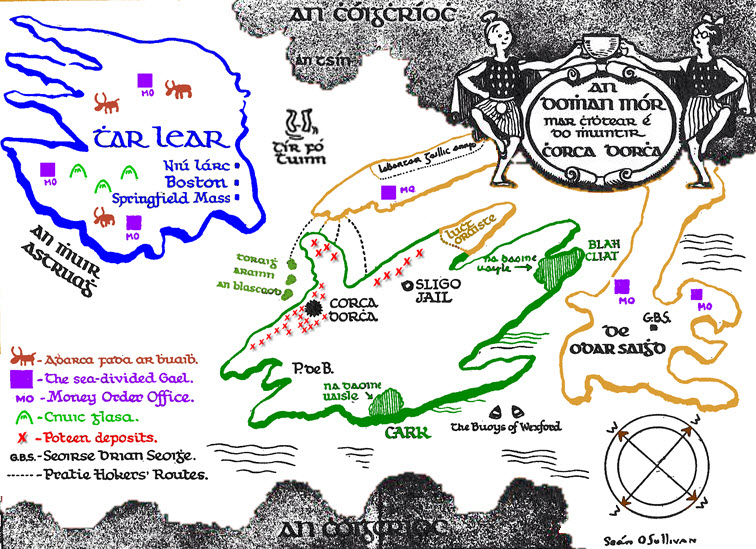

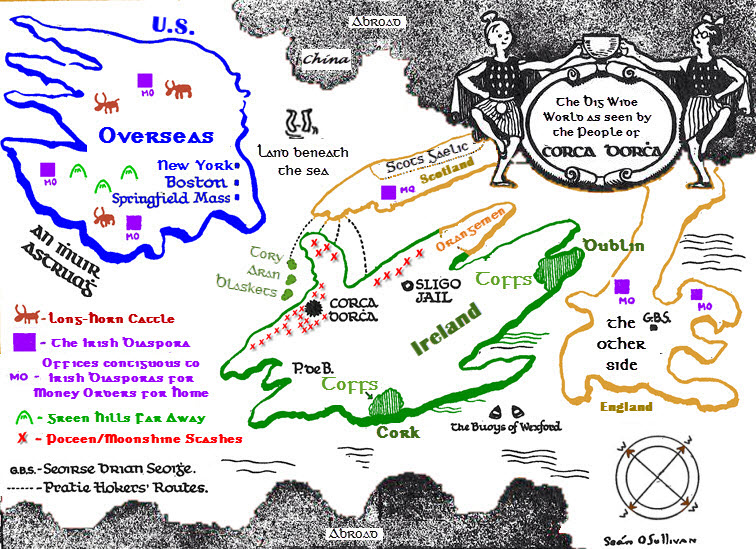

In the front of An BB was a map of An Domhan Mór (The Big World), which is reproduced below at the end of this sectiov. It was important enough to Myles that he referred to it specifically in a letter to his publisher:

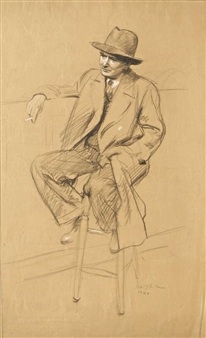

I am developing my original idea for a funny map. It is being drawn by Seán Ó Sullivan and should be a useful addition. (Ó Conaire: 104) The Seán Ó Sullivan in question (who also drew the cover) was a well-known artist friend of Myles. They were both shy men who were too fond of the drop. Both died relatively young — Myles at 54 and Seán at 58.

In spite of its importance to Myles, the map is only available in Irish-language versions of the book (and in Ó Conaire's extremely detailed Irish language exposition on it). It is dropped in the English translations (the first of which did not appear until seven years after Myles' death). I have never seen any reason given for the exclusion of the map. Perhaps it was felt that to translate the map's text would be to bowdlerize it.

But a similar argument applies to the whole book. The Irish language is a central character in An BB. A whole lot gets lost in translation but that is not a reason not to translate it with the best attempt possible to carry over the richness and intricate nuances of the original. And, of course, the whole spirit of the book is to kill sacred cows, not to birth new ones. As far as I can find, no one has put Myles' Map on the Internet either. Thus, it is hidden away from all but the vanishingly small part of the population who would buy the Irish language version of An BB. It may be rushing in where angels fear to tread but it seems like a good idea to publish the map on the Internet. Given Myles' general iconoclasm and the importance he attached to the map, publishing it would seem to be in accord with his wishes. I even took the possibly sacrilegious step of colorizing the map and tarting it up a bit here and there to make the various areas and features stand out better on a computer screen. For the sake of the historical record, a copy of the original monochrome map is posted here. |

The map in reality is a cartoon that essentially stands alone. It has very little got to do with the story or text of An BB. It is full of visual and

verbal puns as explained in the map key at the end of this piece. An Domhan Mór (The Big world) is presented by a pair of dorky Irish dancers in place of the customary dishy colleens. The lands depicted bear little resemblance to the real thing:

Many Irish countrymen, writes Kerby Miller, learned so much about America that they came to see it as scarcely foreign at all. 'Western peasants often knew far more about Boston or New York than about Dublin, Cork, or even parts of their own counties.' Blasket Islanders, as it happens, made a cluster of towns along the Connecticut river centred on Springfield Massachussetts, their new home. (Kanigel: 100) The principal Irish neighborhood in Springfield was a place called Hungry Hill. The name seemingly had nothing to do with conditions in Ireland.

It's likely just a coincidence unrelated to the Springfield neighborhood that an unlikely treasure hunt by Bonaparte late in the novel was to Cruach an Ocrais (Hungry Hill) which in An BB is a sort of Irish Mount Ararat, the resting place of Noah's Ark. Cruach an Ocrais was the higher-ground landing site for the treasure-laden boat of a Corca Dhorcha ancestor who thereby survived a particularly torrential bout of the customary local downpours. The rumored treasure he had with him was the reason Bónapárt 's secret trek up Cruach an Ocrais. He found the treasure and used it to buy the first pair of boots in the area (the prints of which in the mud scared the ever-loving bejeesus out of the locals spooked at the presence of a monster stalking the area). The peelers suspected that Bónapárt's gold came from a murder victim in Galway. Which is how he winds up sentenced to twenty-nine years in the jug ("sa chrúiscín"). |

A Key to Obscurities on Myles’ Map:

Corca Dhorcha: The townland in which An Béal Bocht is set. Corca means race or offspring. It is often used in place names such as Corca Dhuibhne. Dorcha (grammar alternative: Dhorcha) means dark – oíche dhorcha is a dark night. Generally, the Irish don't look on the bright side. It's a trait that comes especially naturally in Corca Dhorcha since Bonaparte informs us that the sun literally never shines on the place. Thus, The Dark Place is aptly named.

And it's a handy transparent disguise. Following novelist convention, Myles asserts that Corca Dhorcha does not refer to any real place but it is hard not to associate it with the aforementioned Corca Dhuibhne, the heart of the Kerry Gaeltacht, the home of Tomás Ó Criomhthain and Muiris Ó Súilleabháin. Ineed, the pretence is dropped momentarily late in the book when the peeler escorting Bonapart to jail orders him: to "Kum along, Blashketman."

The following map of Ireland shows Corca Dhuibhne in the extreme southwest of the country, mentally closer to New York, Boston and, particularly, Springfield, MA than to Dublin.

Corca Dhorcha: The townland in which An Béal Bocht is set. Corca means race or offspring. It is often used in place names such as Corca Dhuibhne. Dorcha (grammar alternative: Dhorcha) means dark – oíche dhorcha is a dark night. Generally, the Irish don't look on the bright side. It's a trait that comes especially naturally in Corca Dhorcha since Bonaparte informs us that the sun literally never shines on the place. Thus, The Dark Place is aptly named.

And it's a handy transparent disguise. Following novelist convention, Myles asserts that Corca Dhorcha does not refer to any real place but it is hard not to associate it with the aforementioned Corca Dhuibhne, the heart of the Kerry Gaeltacht, the home of Tomás Ó Criomhthain and Muiris Ó Súilleabháin. Ineed, the pretence is dropped momentarily late in the book when the peeler escorting Bonapart to jail orders him: to "Kum along, Blashketman."

The following map of Ireland shows Corca Dhuibhne in the extreme southwest of the country, mentally closer to New York, Boston and, particularly, Springfield, MA than to Dublin.

Niú Iarc: Irish does not use the letter "y". Thus "I" replaces "Y" in the Irish phonetic spelling of New York.

De Odar Saighd: Exaggerated Irish phonetic spelling of "The Other Side" – saighd would be pronounced side. "The Other Side" could mean either the geographical other side of the Irish Sea or, more belligerently, the English crowd over there. Calling England or the English De Odar Saighd may be a linguistic dig on Myles’ part at the butchering of Irish placenames during English occupation – which, for instance, turns the meaningful Corca Dhuibhne into the gibberish Corkaguiney and, for that matter, Corca Dhorcha into Corkadorkey. This is a regular relic of international colonialism world wide.

An Mhuir Astruagh: Don't know what it means. It's the name of a sea of some sort – An Mhuir is The Sea. (Explanations or suggestions welcomed.)

GBS & Seoirse Brian Seoighe: One presumes a somewhat obscure reference to George (Seoirse) Bernard Shaw. Don't know where the "Brian" came from or its significance. The surname Seoighe would usually be translated as Joyce rather than Shaw. (Again, clarifications welcomed.)

Pratie Hokers' Routes: Pratie or Tattie Hokers were migrant potato pickers from the northwest coast of Ireland who traveled to Scotland annually under notoriously bad working and living conditions – who would fit right in with the put-upon denizens of Corca Dhorcha.

Sligo Jail: There was a jail in Sligo town from 1823 through 1959. It is not mentioned by name in An BB but Bónapárt winds up serving a 29-year jail sentence for a murder he didn't commit. While being admitted he meets his father, who is being discharged, for the first and only time. Their brief encounter enabled them to compare notes about being "sa chrúiscín" (in the jug), a bit of complicated cross-language slang since the English term wouldn't have the same slang connotation in Irish.

The Buoys of Wexford: A play on the word “buoy” and its homophone "boy" – both word being pronounced the same in Ireland as contrasted with the United States. Co. Wexford (the ancestral home of the Kennedy clan) is the county that occupies the southeast corner of Ireland. The “Boys of Wexford” is a famous rebel song commemorating the 1798 uprising which saw the fiercest and bloodiest conflict in Wexford:

We are the boys of Wexford, who fought with heart and hand

To burst in twain the galling chain, and free our native land.

De Odar Saighd: Exaggerated Irish phonetic spelling of "The Other Side" – saighd would be pronounced side. "The Other Side" could mean either the geographical other side of the Irish Sea or, more belligerently, the English crowd over there. Calling England or the English De Odar Saighd may be a linguistic dig on Myles’ part at the butchering of Irish placenames during English occupation – which, for instance, turns the meaningful Corca Dhuibhne into the gibberish Corkaguiney and, for that matter, Corca Dhorcha into Corkadorkey. This is a regular relic of international colonialism world wide.

An Mhuir Astruagh: Don't know what it means. It's the name of a sea of some sort – An Mhuir is The Sea. (Explanations or suggestions welcomed.)

GBS & Seoirse Brian Seoighe: One presumes a somewhat obscure reference to George (Seoirse) Bernard Shaw. Don't know where the "Brian" came from or its significance. The surname Seoighe would usually be translated as Joyce rather than Shaw. (Again, clarifications welcomed.)

Pratie Hokers' Routes: Pratie or Tattie Hokers were migrant potato pickers from the northwest coast of Ireland who traveled to Scotland annually under notoriously bad working and living conditions – who would fit right in with the put-upon denizens of Corca Dhorcha.

Sligo Jail: There was a jail in Sligo town from 1823 through 1959. It is not mentioned by name in An BB but Bónapárt winds up serving a 29-year jail sentence for a murder he didn't commit. While being admitted he meets his father, who is being discharged, for the first and only time. Their brief encounter enabled them to compare notes about being "sa chrúiscín" (in the jug), a bit of complicated cross-language slang since the English term wouldn't have the same slang connotation in Irish.

The Buoys of Wexford: A play on the word “buoy” and its homophone "boy" – both word being pronounced the same in Ireland as contrasted with the United States. Co. Wexford (the ancestral home of the Kennedy clan) is the county that occupies the southeast corner of Ireland. The “Boys of Wexford” is a famous rebel song commemorating the 1798 uprising which saw the fiercest and bloodiest conflict in Wexford:

We are the boys of Wexford, who fought with heart and hand

To burst in twain the galling chain, and free our native land.

Sources

- Myles na gCopaleen (Brian Ó Nualláin). 1941/1999. An Béal Bocht.

- Myles na gCopaleen (Brian Ó Nualláin; Flann O'Brien); Patrick Power trans. 1973. The Poor Mouth.

- Ó Conaire, Breandán. 1986. Myles na Gaeilge: Lamhleabhar ar Shaothar Gaeilge Bhrian Ó Nualláin (Irish Myles: Handbook of the Irish Works of Brian O'Nolan).

- Ó Criomhthain, Tomás. 1929/1973/2002. An t-Oileánach (The Islandman).

- Ó Grianna, Séamus. 1942/1986. Nuair a Bhí Mé Óg (When I Was Young).

- Ó Súilleabháin, Muiris. 1933. Fiche Bliain ag Fás (Twenty Years A-Growing).

- O'Leary, Philip. 2010. Irish Interior: Keeping Faith with the Past in Gaelic Prose 1940-1951.

- Sayers, Peig. 1936. Peig .i. A Scéal Féin (Peig, i.e., Her Own Story).

- Sayers, Peig. 1939. Machtnamh Sean-Mhná (An Old Woman's Reflections).